Tiemann’s art thrives on paradox of being in the world but not of it

By Marcia Goren Weser (in San Antonio Light, 1988)

T.S. Eliot once wrote about returning to a place and seeing it again, as if for the first time. Seeing it anew. More than the sense of deja vu, of having seen a place before, Eliot was speaking of a kind of circularity, that having traversed an unexpected path, we come to that beginning point which is not quite where we started. Because of the journey, the place has changed for us. Or perhaps we have changed.

That circularity, and the process involved in getting there, is what Bob Tiemann’s new show at the Carver Cultural Center’s gallery is about. It is also about ironic dichotomies, as well as anachronisms that perpetuate themselves. It is about institutional games that are played in the name of “Art,” and the anguished incongruities in the making of that art. It is about context and environment.

“I don’t want art to be isolated,” says the artist. “I don’t want to create a specific object. Art is only art if the viewer says so, if the viewer gives meaning and value to the piece. Viewers make art, artists just make stuff. It’s like I present myself and if I’m not accepted, then I go on to someone else.”

These works, unlike those in his show earlier this year at the Blue Collar Gallery, are titled: “Dancing Sam,” “This Is Not a Pipe,” “Painted Pain,” “Roll Model,” “Color Reduction”—to name a few. Many are plays on words: roll for role, pain for bread (en Francais); others refer to dual meanings: color as hue as well as race, pipe for its function as well as its shape.

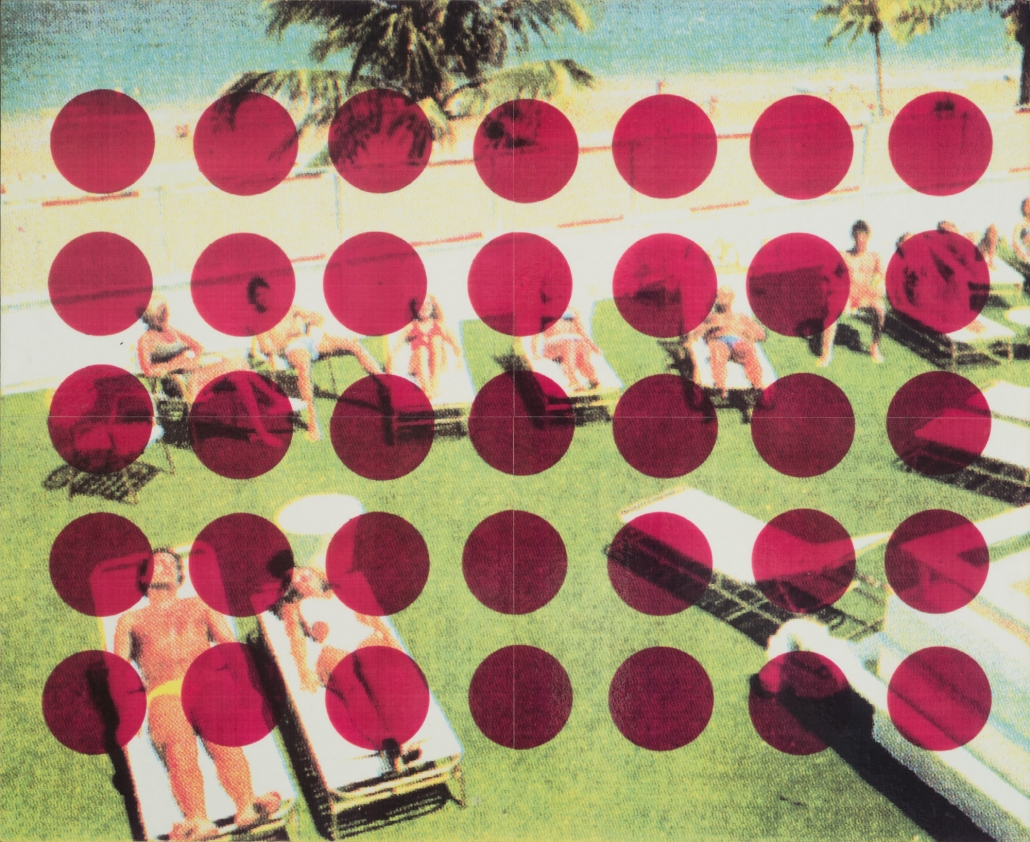

Language and vision, social context and value-laden cultural interpretations give meaning to these everyday objects and color-xeroxed photographs which comprise the show. A tacky plastic handbag, opened and filled with cement, is called “Hard Life.” The tough realities of women’s’ economic hardships come home in a reference to dependence on fashion as one (socially acceptable) means of overcoming such (socially imposed) limitations.

“Food Chain” features a milk carton atop a stepladder with grass on the floor and cow patties on each step. “Craving” places a swathed chopping knife next to a newspaper clipping about recent discoveries about Van Gogh’s alleged food picas for eating paint and turpentine.

Tiemann has even placed color polaroids of these three dimensional works in the show. The object and the photograph of the object in another context (other than this gallery setting) give a certain surreal quality to both. What is real and why? Is one more real than the other? How has placement changed the meaning of the object?

*****

“The History of Western Art” is a series of photographs of a cow (in the distance) framed by a torn piece of paper held by an outstretched arm. Cowboy art in one of its many guises? A comment on the trompe l’oeil aspects of perspective as a bankrupt technique for “reproducing reality?” Or about how artists choose what to include in a work of art?

“Good art makes you think,” commented Tiemann in a recent interview. “It is about what you, the viewer, make it about. The artist’s intention is not important: I am opposed to the notion of ‘significant form,’ that is, one point of view is more important than others or is the correct view … I keep ‘selections’ ambiguous, images that will allow for the most meanings.”

The irony is in the ambiguity, for it does exist in these works. Yet by the very nature of making art, the artist must make selections (as well as omissions) and in the very act of doing so preclude some (though not all) interpretations of that work.

“About the same time that [Roland] Barthes wrote of the death of the author in literature, [Marcel] Duchamp was intimating the same thing about art,” said Tiemann. “I want people to make connections that are surprising to them when they look at my work. Foucault talked about ending up being someone you weren’t when you started out … for me that is a place where all opposites meet, in a very unconscious place that is also very sexual, because it bridges gender. It also bridges race and culture and economics, for we can only ‘be’ in this world when we begin to transcend the superficial gaps that separate us, when we really feel what another person feels.”

The viewer must take a Kierkegaardian “leap of faith” and suspend expectations and judgments about what is “art” and what separates us, one from the other. Tiemann is asking us to go beyond simple answers and accepted assumptions about art, as well as what it is is to be a man or a woman; to be black or brown or yellow or white; to be rich or poor.

“I want to turn everything upside down,” the artist continued. “Art is now a commodity, to be bought and sold. I want to make art for a little while—not forever; the system (galleries and museums) … is interest only in maintaining its own power … that is the big issue.”

Yet Tiemann himself, a professor of art at Trinity University, is part of the system which produces “artists”—accredits and legitimizes their right to be in that system—as well as produces art objects. He acknowledges all this, yet sees the inexpensive, fragile, and transient nature of his materials as obviating, to some extent, this problem. Tiemann’s art is refreshing in that it even mocks itself.

Paradox has always been inherent in Tiemann’s work. Here he faces the paradox of being in the world and yet not of it. Of making sense of what is self-evident yet remaining self-conscious. Making good art, as Tiemann invariably does, is much like making a good life: to be unerringly true to one’s own vision without becoming embittered in the face of one’s own (very human) frailties and inconsistencies. That is Tiemann’s ultimate leap of faith.